ABOUT THE BLOGGER

- Beti Ellerson

- Director/Directrice, Centre for the Study and Research of African Women in Cinema | Centre pour l'étude et la recherche des femmes africaines dans le cinéma

Translate

Search This Blog

05 December 2024

From Kaddu Beykat to Pumzi: Commemorating World Soil Day, 5 December

04 December 2024

Omonike Akinyemi launches a crowdfunding campaign on Spotfund for the film “Emancipado”

Description

"Emancipado", an episodic feature film that tells the story of a fictionalized Afro-Cuban woman, Ifemorena, who dreams to return to Africa. "Emancipado" delves into the circumstances that give rise to Ifemorena's dream -- the Lukumi community and flamenco family to whom she belongs is in crisis.

For more information on the crowdfunding campaign and to make a contribution:

02 December 2024

2 December: International Day for the Abolition of Slavery | 2 décembre : Journée internationale pour l'abolition de l'esclavage

13 November 2024

African women and the camera as weapon: “this is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity.”

This project has as objective to bring together voices from diverse experiences of these women who use the camera as their weapon, who make films that reveal the myriad challenges on the path to peace, justice, democracy, freedom and positive change.

In France, Horria continues her struggle against political violence against women and religious extremism. More than a decade after the release of Algérie en Femmes in 1996, her film continues to be relevant as evident in the venues to which she is invited to screen and discuss the film. Notably, at the 2008 meeting of the French-based Union des Familles Laïques (Mouvement laïque d’education populaire) of which she holds the post of president of the UFAL-Saint-Denis.

Horria also presented Algérie en Femmes at the Maison René-Ginouvès, Archéologie et Ethnologie in November 2009, and in 2007 the film was featured at two events: as part of International Women’s Day she participated in the colloquium, Rencontre féministe sur les Femmes et l'Algérie organized by the Marche Mondiale des Femmes contre les Violences et la Pauvreté, and at the Festival Cineffable at which the film won the ProChoix Award—all venues are based in France.

Also during our conversation Horria had this to say regarding Algérie en femmes:

Nadia el Fani: For me, everything is urgent; everything goes forward at the same time. Everything is connected.

Following her public statements on Hannibal television, filmmaker Nadia El Fani has been the object of an extensive campaign of verbal and physical threats on certain Facebook pages. We, Tunisian citizens committed to the freedom of conscience, belief and worship, declare by this, our full support of Nadia El Fani. We are stating that by her right to express her non-belief in God, she rejects any attempt to impose obstacles to her freedom of conscience by those who claim to adhere to a political Islam. We, Tunisian citizens hereby express our absolute indignation at the threats of physical violence and the verbal rampage against Nadia El Fani.

We believe that the current political rise of Islamists, the repeated assaults against women whose dress does not conform to a so-called "Islamic morality", the political manipulation by the mosques, and the calls to murder for "blasphemy", necessitate the demand for greater vigilance. In this current climate there is especially the need for solidarity with all those who have the courage to not yield to the law of terror and the submission to silence.

We believe that a society is either tolerant or it is not. Freedom of conscience is not divisible. In the same way that wearing the veil and a beard should be allowed and respected, an individual has the right to declare that he/she "does not believe in God." If today we give in to the threats of violence against those who declare their atheism, tomorrow the threats will be against those among us who are non-practicing Muslims, and the next day those among us who are practicing Muslims but who do so in a manner not acceptable to the extremists!

Rumbi Katedza: I was approached by producer David Jammy to direct a film about how a community that has experienced conflict and violence is dealing with the repercussions, and how or if they are able to move on. The producers and I decided to work with a group that was already working on a community-healing project, and through my research, I learned a lot about the terrible things that had happened to every day people during the 2008 Zimbabwean harmonized elections. It was an eye-opener, a kind of education in fear, and how fear can paralyze people and make it impossible to live their lives to their full potential.

27 September 2024

Festival féministe sénégalais - Jotaay Ji - au Musée de la Femme Henriette Bathily - 27-29 septembre 2024 avec une soirée ciné

Waxtaan, des panels, des ateliers créatifs, des projections de films, des activités centrées sur le bien-être, etc.

Aux habituels espaces non mixtes réservés aux femmes s’ajouteront, cette année, des espaces réservés aux adolescentes pour discuter de préoccupations qui les concernent plus directement.

Des espaces innovants seront également dédiés à des discussions féministes sur la construction sociale des masculinités."

Les membres du Collectif JAMA

26 September 2024

Focus: Nadia El Fani - Programa de Cortos Nadia El Fani - Mostra de València Cinema del Mediterrani - 24 oct - 3 nov 2024

Cinema del Mediterrani

24 oct - 3 nov 2024

https://lamostradevalencia.com/edicion-2024/focus-2024/

Selección de trabajos de Nadia El Fani en formato cortometraje.

«Pour le plaisir»

«Du côté des femmes leaders»

«Tanitez-moi»

«Tant qu’il y aura de la pelloche»

«Unissez-vous, il n’est jamais trop tard!»

21 September 2024

Seuls en Scène 2024 presents Voyage of the Sable Venus by Robin Coste Lewis read by Alice Diop

Seuls en Scène 2024 presents Voyage of the Sable Venus by Robin Coste Lewis read by Alice Diop

Princeton Lewis Center of the Arts

21 September 2024

At Seuls en Scène, Alice Diop will read the text of Voyage of the Sable Venus in a work-in-progress version of a performance scheduled to premiere at Festival d’Automne/MC93 Bobigny in Fall 2025.

https://arts.princeton.edu/events/seuls-en-scene-2024-presents-voyage-of-the-sable-venus-by-robin-coste-lewis-read-by-alice-diop/

Image: Lewis Center of Arts

16 September 2024

Oscar 2025 : Dahomey de/Mati Diop représentera/will represent le Sénégal pour/for Best International Feature Film category

Dahomey de Mati Diop représentera le Sénégal à l'Oscar 2025 du meilleur film international

Dahomey by Mati Diop selected to represent Senegal for the Best International Feature Film category at the 2025 Oscars

Novembre 2021, vingt-six trésors royaux du Dahomey s’apprêtent à quitter Paris pour être rapatriés vers leur terre d’origine, devenue le Bénin. Avec plusieurs milliers d’autres, ces œuvres furent pillées lors de l’invasion des troupes coloniales françaises en 1892. Mais comment vivre le retour de ces ancêtres dans un pays qui a dû se construire et composer avec leur absence ? Tandis que l’âme des œuvres se libère, le débat fait rage parmi les étudiants de l’université d’Abomey Calavi.

November 2021, twenty-six royal treasures of Dahomey prepare to leave Paris to be returned to their land of origin, Benin. In 1892, with several thousands of others, these oeuvres were pillaged during the invasion by French colonial troops. How then will the return of these ancestors, to a country which has had to reconstruct and rebuild itself since their absence, be received? While the soul of these oeuvres frees itself, the issue is hotly debated among the students at the University of Abomey Calavi.

11 September 2024

Nadine Otsobogo, Filmmaker Make Up Artist is a featured speaker at GLF Africa 2024: Greening the African Horizon

https://africanwomenincinema.blogspot.com/2023/09/nadine-otsobogo-tout-est-lie-its-all-connected.html

Nadine Otsobogo crée le Festival du Film de Masuku - Nature et environnement | Nadine Otsobogo creates the Film Festival of Masuku - Nature and Environment (Gabon)

https://africanwomenincinema.blogspot.com/2013/08/nadine-otsobogo-cree-le-festival-du.html

(Re)Discover Nadine Otsobogo

https://africanwomenincinema.blogspot.com/2011/05/la-parole-nadine-otsobogo.html

01 September 2024

Cine Fem Fest - The African Film and Research Festival - Call for Applications for a Writing and Creation Workshop

Call for Applications for a Writing and Creation Workshop: Intersections: Genre(S), Art and Action-Research

This writing workshop, which will be held in the last trimester of 2024, will bring together a group of around fifteen carefully selected participants of artists, political decision-makers and researchers who will work together to produce artistic and/or academic works that shake up the established order in terms of knowledge production based on rigorously documented empirical data or on artistic works. The week-long writing workshop aims to bring together teachers, researchers, feminist activists and artists to produce a collective output.

Deadline September 2, 2024.

For full details go to: https://cinefemfest.com

19 August 2024

WildTrack Newsletter 2024 - Issue 1.24 published by the Women Filmmakers of Zimbabwe

09 August 2024

Global Cinema Meets Female Empowerment At IIFF2024 - Harare, Zimbabwe - PRESS RELEASE

The International Images Film Festival For Women (IIFF) 2024 Catalogue - Harare, Zimbabwe

Follow the link to download the catalogue (23.4mb) on the right column of the page:

https://www.icapatrust.org/news/iiff-2024/

14 July 2024

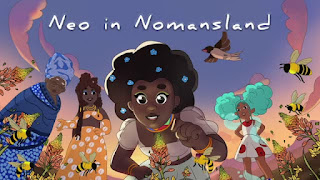

“Neo in Nomansland” (Women in African Animation)

26 June 2024

Alice Diop filmmaker-sociologist-activist : «Nous, on vote» (We're voting)

Source and image: Libération, 26 juin 2024

24 June 2024

Closeup: The Africas/Diasporas of Women in the Evolution of a TransAfrican Film Practice and Critical Inquiry curated by Beti Ellerson - Black Camera: An International Film Journal 15. 2 (Spring 2024)

Black Camera: An International Film Journal

https://doi.org/10.2979/blc.00014

Excerpted from introduction:

The objectives of the Close-Up, The Africas/Diasporas of Women in the Evolution of a TransAfrican Film Practice and Critical Inquiry: to recover, to chronicle, to affirm, to reimagine even, African/Diasporan women’s cinematic world-making, indeed self-making—envisioning the manners in which they devise, create, make, a space, a universe, a domain, a world; within which they may tell/relate their stories—storytelling as a project of world-making through cinema.

The Close-Up asks questions regarding the tenets of an African/Diasporan cinematic practice/tradition shaped by women: its beginnings, the forces that compelled, facilitated and informed it, the requisite approaches needed to formulate it, and the propositions on which to explore its cultural, political, and social manifestations.

The title “The Africas/Diasporas of Women in the Evolution of a TransAfrican Film Practice and Critical Inquiry” calls attention to the multiplicity of locations, providing a place for the explication of African/diasporic histories (historical and new Diasporas), as well as an elaboration of the peregrinations as well as the negotiation of hybrid, indeed symbiotic, identities of so many of these women.

The Close-Up comes together under myriad themes, in order to draw from the intersectional, multifarious aspects of women’s transAfrican film practice, histories and critical inquiry.

“(Re)imagining cinematic histories of Africa: African women, cinema and the tale of Kadidia Pâté”, offers a prelude of sorts, relating the story of Kadidia Pâté’s first experience with cinema, as a colonial subject in Mali in 1908, and later in 1934 when she first sets foot in a movie theater, during which the specifics of her engagement with cinema unfolds, related by her son, the inimitable griot, storyteller-historian Amadou Hampâté Bâ.

The introductory essay, “Women’s transAfrican cinematic practice and activism: Mapping the trajectory of an African women’s cinematic consciousness,” conceptualizes the transAfrican nature of women’s cinematic practice and critical inquiry. In so doing, it traces key historical, political and cultural movements of the twentieth century that stimulated the artistic and intellectual sensibilities of the trailblazers who set the course moving forward. The discussion of these pioneering women—several of which are featured in this section—puts into focus the multiple environments that shaped their choices, and offered the requisite context in which to study, work, live and imagine future worlds for themselves and Africas/Diasporas.

“Building a legacy: archiving, curating, disseminating, producing, preserving, African-diasporic cinematic experiences,” brings together a discursive profile of cultural workers who have as mission, to build a legacy by creating, archiving, disseminating, curating, preserving, the collective experiences of cinematic Africas/Diasporas as well as to uphold its oral traditions through visual storytelling.

“Alternative Discourses: theorizing lived experiences in African women’s cinematic practice, meaning-making and shaping of knowledge,” draws its main heading from the words of Togolese international lawyer-filmmaker, Anne-Laure Folly Reimann, who describes the dialogue of the women in her films as “alternative discourses”: beyond the analysis of things, they live them. This appropriately applies as well to the women in front of the screen, as scholars, critics, organizers, advocates, activists and behind the camera as filmmakers. The women presented in this segment, work at the intersection of critical meaning-making and the cinematic practice of counter-hegemonic production of knowledge.

“Mediating diasporic cinematic experiences and practice” probes African women’s cultural identity and social location as diasporic experience. Thus, the section explores the ways that they grapple with exilic, traveling identities in their cinematic practice, research and analysis. It examines as well the multiple ways that “the duty of memory” plays out in the films and visual projects of the women selected to represent this segment. The painful question: Do they remember us? gives rise to the emotional reconnecting needed “to no longer feel hurt” by the tear of separation from dislocation during the trans-Atlantic slave trade and enslavement of Africans in the Americas. The Sankofa proverb: “it is not taboo to go back and retrieve what you have forgotten or lost”, becomes the leitmotif of so many of the stories of Africans who have left and seek to return, whatever the circumstances.

“Critiquing Africas/Diasporas: Intersecting dialogues,” presents a compilation of interviews by Falila Gbdamassi with several celebrated filmmakers, organizers, film critics/activists who navigate within the world cinema landscape—with Africa and the Diasporas on their minds.

“Reconciling Africas, Identities and Diasporas,” prepares the reader of a caveat, but insists it is not a polemic. The title speaks for itself. Discourses, questions, responses, on the very nature of Africa, the African, are not new. Hence, this section returns to a moment in the past when, “in the mouth the teeth sometimes bite the tongue” as a Burkinabe adage goes. In 1991, at the start of the landmark Women’s Meeting at FESPACO, confusion ensued at the announcement that “all non-African women leave the room,” which, as it turned out included diasporan women. Compiled here are diverse responses on both sides of the debate. Thus, by introducing this section, employing in this proverb all the conflicts and anxieties that the event revealed, provides an armature of sorts, in which to continue the conversation raising other stakes and ultimately returning to this pivotal question and its incessant pursuit towards an answer.

The final piece on this theme repositions discussions around African subjectivities, as well as deconstructs the very notion of an African ontology, including questions of ethnicity. Thus, this section considers the positionality of white South African women, especially as it relates to white privilege and the importance of interrogating whiteness. The questions around identities in South Africa focus as well on the Bo-Kaap community largely populated by the Malay diaspora. During this same conversation around complexities of identity, this segment explores the dual positionalities of Arab/African women. And finally, it probes the renegotiated identities of first and second generation diasporans in search of belonging, home, place.

The Close-Up is in the memory of Sarah Maldoror and Safi Faye.

22 June 2024

Pauline Mvele Nambané, founding director of the Festival International "Cinéma & Liberté" Libreville, Gabon

Drawing from several sources, following is the vision of the Festival International "Cinéma & Liberté" and a portrait of founding director of the Festival International Cinéma & Liberté, Pauline Mvele Nambané. Translation from French by Beti Ellerson

Sources: Marie Dorothee (gabonactu); Steven Mpono (7joursinfo-com) and video conversation with Pauline Mvele Nambané by Urban FM 104.5 La Station Urbaine and image from its YouTube channel.

A culmination of years of dreams and fine-tuning of ideas, the International Cinema and Freedom Festival of Libreville finally comes to fruition. The activities were detailed on Friday the 4th of June 2024 during a press conference which was held at the French Cultural Center in the presence of an array of invited guests.

The 1st edition of the International Cinema and Freedom Festival of Libreville in Gabon will take place from June 24 to 29. Film screenings followed by Q&A, will be held each evening from 18h30 free of charge at the Baie des Rois. Fittingly, Laurence Ndong, the Gabonese Minister of Communication and Media, is the patron of this 1st edition.

During her inaugural address Pauline Mvele Nambané, founding director of the festival, whose vision of the festival is to create a space for an intergenerational exchange, presented the objectives of the film event. She emphasized that the festival, which was the outcome of a collaboration between the Association Gabon Ciné Doc and Clybe Nambané Production, aims to promote, education through images, human rights and freedom of expression. These objectives will be achieved through film screenings, training workshops and other cultural activities. In addition, an international conference on the theme “cinema and citizenship” will be held.

In addition, the festival aims to promote African film heritage. Pauline Mvele Nambané noted that the 1st edition will celebrate and pay homage to many of the great filmmakers of African and Gabonese cinema such as: Charles Mensah, Philippe Maury and Pierre Marie Ndong, as well as Henry Joseph Koumba Bididi, Imunga Ivanga and Prince De Capistran.

Translation from French of the video interview by Urban FM 104.5 La Station Urbaine

(L’interview YouTube originale en français, ci-après)

The emergence of the Festival International "Cinéma & Liberté"

The festival has a particular interest in films on human rights, freedom of the press and best practices of democratic governance. The goal is to educate, to inform people about freedoms and rights. We are convinced that cinema is a powerful tool for educating, awareness building and a means to change behavior. Through this festival we want to contribute to educating the Gabonese population.

Pauline Mvele, director of the Festival International "Cinéma & Liberté"

I am a filmmaker and throughout the years I have made several documentaries that focus on social themes. I created an association with friends and for several years we toured the schools to do film screenings. So this festival presents a bit of a culmination of everything we have done; and in particular, of my filmography, of my commitment towards these themes.

Why the focus on the protection of liberties?

Because I believe that every human being has a mission and we are not here by chance. As a filmmaker I cannot just stand by. When you look at my filmography you will notice that I decided not to remain silent and inattentive regarding certain situations that I observe in my society. So I give voice to these people so that the situations that they live are known and that another perspective can be given.

Violence against women, giving testimony

I received a lot of testimonies when preparing to make the films. With the film, Mivova Yato, which is a documentary about gender-based violence, I collaborated with an association. I received a lot of testimonies but at the time of filming many withdrew, after having agreed, at the moment of the filming they “remove their body,” as we call it. But I do understand perfectly. It’s not easy. Sometimes when one experiences a situation and talks about it with two other people it's okay, but to do so in front of a camera, to say it to the whole world. I really do admire all the people in my films who had the courage to testify, with their faces uncovered. Personally I am not sure if I had experienced certain situations that I would have dared to talk about it. But it is also the role of the filmmaker to provide the environment that instills a sense of confidence and trust with the interlocutors. I do feel that I create an environment where people feel comfortable to confide in me.

What is your method for creating this trust?

I don't know if I would say that I have a method but I think it is because I really like people, I know how to listen to people, I know how to look at them and I am sentient of their situation. To give an anecdote of a great filmmaker, who said that one should film the people one loves and in so doing, inevitably something comes out positive for you.

Accroche-toi, the first documentary film

It was my first documentary, which I continue to hold very dear. However, when I look at it with hindsight I say to myself that I could have done better, but it was not about the technology at the time. No, that has nothing to do with it. I believe that’s often the big mistake people make. To say, “Oh yes I have the most efficient camera so I could make a good film.” It’s not true. Someone can make a good film with a cell phone. So it is one’s cinematic practice that determines the results. I was trained on the job and I had my background as a journalist as well. So yes, there is cinema there, but there is also a lot of reportage in the film. I think today, now 10 years later, I would have made this film differently, especially as the characters were really strong.

Perhaps a remake?

Unfortunately, no. When I watch the film now I am touched, because Libreville is no longer like that… I am taking advantage of your platform to talked about what happened. The three women who you see there, in the film, two of them died. That makes it even more important to talk about the people who are living with HIV, the situation has regressed a great deal in Gabon. Today we need to talk about the fight against AIDS. In Gabon there is no longer awareness, no one is taking charge of the problem. It seems that HIV is touching a progressively younger population, the 18-30 year-old population which are carriers of the disease and it's very serious because it is an illness which is still incurable. There is still no definitive cure so there is this film and it's important that it exists. And it's also an opportunity to pay tribute to these people who agreed to testify openly. Today there are those who are no longer with us, but they continue to live, one could say, because of this film.

In 2014, you made Sans famille, a documentary that received the award for best documentary at the International festival of cinema and audiovisual of Burundi. How did you established contact with the actual and former prisoners or certain prisoners?

Actually with most of my film projects, the first thing that I do is to familiarize myself on the subject, I start collecting documents, I read a lot of books, watch other films and then I talk about it to a few trusted people. I tell them that I am working on a project and ask them if they are also familiar with the subject, I meet with associations that support the cause to see if perhaps they have leads.

Films focusing on Gabon

All of my films take place in Gabon and these films that I have made actually give me another face of humanity…they allow me to be even more sensitive and give me the force to say that I am on the right path and that I must continue.

Sans famille, did you want to highlight prisoners’ rights

Yes. The central prison of Libreville was built during colonialism, designed for an occupancy rate of 300. At the time that I made the film there were more than 5,000 people. That’s not normal. Because someone made a mistake, they should not have to live in inhuman conditions. And the prison system should assist those who are there so that when they are released they can restart their lives. But nothing is done. I know of initiatives in other countries that are commendable. Every morning prisoners were taken out in order to do farming, the prisoners ate what they cultivated, they ate healthy food. The prison sold the products and saved the earnings and when the prisoners were released they benefited as well. There are initiatives such as these. But when people are locked in their cells 24/24 hours, year after year and nothing is done. When a young person is locked away for six months because they stole something, when they are released they become assassins. They have hardened in general. They become hardened having been around other notorious prisoners, there is a mixture of people of varying crimes and sentences. So yes, it is about the struggle for prisoner rights.

And this first edition of the Festival International "Cinéma & Liberté"

The festival is free to all. The aim of the festival is to have cinema meet the public. In addition to film screenings there will be training workshops. There will be roundtables, an international conferences. There will be five Masterclasses (see details below).

There are two other people who come from Morocco and Côte d’Ivoire. In any case we expect big names in African cinema. I would like to thank the French Institute who agreed to support us on this first edition as well as others.

Marie Dorothée of gabonactu gave the following details of the Masterclasses:

“Writing, directing and producing the documentary” led by Natyvel Pontalier, Gabonese director and Laurent Bitty, Ivorian director-producer and Kalid Zairi, director/producer from Morocco.

“Actorat” and “How to succeed in a good production” will be led by Rasmané Ouedraogo, one of the main actors of the series “Bienvenue à Kikidéni”, which is currently broadcast on Canal +.

“From idea to realization and production of a series” by Aminata Diallo Glez, director of successful series: 3 hommes 1village, 3 femmes 1 village, Super flics and Bienvenue à Kikideni.

“The management of cultural projects” by Abdoulaye Diallo and Alpha Bah, both festival directors.

“The structure of the scenario” by Imunga Ivanga. This master class will lead to the production of a film which will be screened during the next edition.

09 June 2024

Dr. Estrella Sendra discusses the Legacy of Safi Faye with The African Cinema Podcast

Dr. Estrella Sendra discusses the Legacy of Safi Faye with The African Cinema Podcast

Drawing directly from the article “”I dared to make a film: A tribute to the life and work of Safi Faye” Black Camera Fall 2023*, Dr. Estrella Sendra discusses the Legacy of Safi Faye with The African Cinema Podcast

https://open.spotify.com/episode/3KbfNderfGDcoERMVoP4Gt

*See link to Black Camera article by Beti Ellerson

https://africanwomenincinema.blogspot.com/2023/12/safi-faye-i-dared-to-make-a-film-tribute-to-her-life-and-work.html

Image: Beti Ellerson

Ruth Hunduma, laureate of the Hypatia Golden Award for the documentary The Medallion at the 10th edition of the Alexandria Short Film Festival (ASFF) in Egypt

Ruth Hunduma, laureate of the Hypatia Golden Award for the documentary The Medallion at the 10th edition of the Alexandria Short Film Festival (ASFF) in Egypt

The documentary portrays the filmmaker's mother, a survivor of the Red Terror in Ethiopia which left hundreds of thousands of victims. A powerful testimony to a nightmare that remains unknown in the West.

Excerpted from an interview with Ruth Hunduma by Nicolas Bardot at lepolyester.com

The idea for the film came from a short story I wrote when I was at university called The Medallion, about the genocide of the Red Terror, from the point of view of my mother. In 2022, during the Tigray War, as I was preparing to travel to Ethiopia to spend time with my mother, my producer suggested that I re-visit the story of The Medallion. Within the context of the civil war at the time, it was the perfect context to open up a discourse not only about the war itself, but also about Western media bias during the Red Terror genocide, which unfortunately, like the Tigray war, attracted little or no attention. I started filming it myself with the cameras that I had on hand; and bit by bit, I started constructing the DNA of the film.

08 June 2024

Tsitsi Dangarembga (ICAPA), Souad Houssein (OPAC), Zanele Mthembu (SWIFT), three women-helmed organizations collaborate to advance and promote women and cinema in Africa

The signing ceremony for the memorandum of understanding between (Institute of Creative Arts for Progress in Africa) ICAPA Trust, The Pan-African Observatory for audio-visual and cinema (OPAC) and Sisters Working in Film and Television (SWIFT) of South Africa was held recently, in Harare. Tsitsi Dangarembga, the signatory of the memorandum, had this to say:

“This signing ceremony follows meetings between Souad Houssein, founding director of OPAC, Zanele Mthembu, the acting programme manager of SWIFT and myself, in our capacities as representatives of our three organisations. These meetings took place in Harare last year, during the 2023 edition of the International Images Film Festival for Women (IIFF).”

Today marks a historic moment where together, we strive to break barriers and champion equality in storytelling. The Zimbabwe’s Institute of Creative Arts for Progress in Africa (ICAPA) Icapa Trust, Fance's Pan-African Audiovisual and Cinema Observatory (OPAC) and South Africa’s Sisters Working in Film (SWIFT) sign an MOU, paving the way for a transformative collaboration in film and television across Africa. This partnership aims to foster capacity building of African and African-descended women filmmakers through skills development, film promotion and viewing of women friendly films in the region to amplify diverse voices, facilitate joint and individual projects and the establishment of a pioneering International Images Film Festival for Women (IIFF)

As noted in the ICAPA December 2023 newsletter, “the objective of this historic meeting of three organizations led by African women was to draft and sign an agreement to collaborate in the areas of training, women’s film festivals, including African women’s film awards and fundraising.”

Text:

The Standard. “Icapa, OPAC and Swift sign MoU” by Tendai Sauta, June 4, 2024

ICAPA News, 20th edition of IIFF wows Harare, December 12, 2023

07 June 2024

DIASPORAS : Cinemateca Brasileira apresenta a mostra 80 anos de Zezé Motta - the Cinemateca Brasileira presents the exhibition 80 ans de Zezé Motta (the 80 years of Zezé Motta)

Entre os dias 7 e 9 de junho, a Cinemateca Brasileira apresenta a mostra 80 anos de Zezé Motta, comemorando a importante contribuição da atriz ao audiovisual brasileiro. Artista plural, com trabalhos no teatro, na música, na televisão e no cinema, a atriz também se destaca pelos anos de luta por maior representatividade de artistas negros e negras nas artes.

From 7-9 June the Cinemateca Brasileira presents the exhibition 80 ans de Zezé Motta (the 80 years of Zezé Motta) celebrating the important contribution of the actress in the Brazilian audiovisual landscape. Zezé Motta's multifaceted practice as artist spans theater, music, television and cinema, she is also known for her activism throughout the years towards a greater representation of black artists.

04 June 2024

Mujeres por África : ELLAS SON CINE 12 - 2024 Madrid (They [women] are cinema) Ramata-Toulaye Sy, Myriam Uwiragiye Birara, Sofia Alaoui, Rosine Mbakam, Kaouther Ben Hania

Mujeres por África organiza esta muestra de cine para dar visibilidad al audiovisual femenino del continente

Ellas son Cine, la muestra de películas dirigidas por mujeres africanas, regresa un año más a la Sala Berlanga de la Fundación SGAE en Madrid (c/Andrés Mellado 53) en su decimosegunda edición, del 4 al 8 de junio con proyecciones a las 19.30 horas. Y lo hace con cinco películas de directoras que recorren el continente africano de este a oeste, de norte a sur: Banel et Adama, de la senegalesa Ramata-Toulaye Sy; The Bride, de la ruandesa Myriam Uwiragiye Birara; Animalia, de Sofia Alaoui, originaria de Marruecos; Mambar Pierrette, de la camerunense Rosine Mbakam, y, desde Túnez y en cooperación con Arabia Saudí, Les filles d’Olfa, de Kaouther Ben Hania.

Mujeres por África [Women for Africa] organizes this film exhibition to give visibility to women audiovisuals on the continent

Ellas son cine (They [women] are cinema) of the Fundación Mujeres por África returns to the Sala Berlanga of the SGAE Foundation in Madrid for its 12th edition from 4-8 June with five films that reflect the social condition of women throughout the continent from east to west, from north to south. Films by women from Senegal, Rwanda, Morocco, Cameroon and Tunisia: Banel et Adama by Senegalese Ramata-Toulaye Sy; The Bride by Rwandan Myriam Uwiragiye Birara; Animalia by Sofia Alaoui from Morocco; Mambar Pierrette by Cameroonian Rosine Mbakam, and from Tunisia in cooperation with Saudia Arabia, Les filles d’Olfa by Kaouther Ben Hania.

31 May 2024

Farida Benlyazid and Moroccan Cinema by Florence Martin

Description

This book project unfolds and analyzes the work of Moroccan director, producer, and scriptwriter Farida Benlyazid, whose career extends from the beginning of cinema in independent Morocco to the present. This study of her work and career provides a unique perspective on an under-represented cinema, the gender politics of cinema in Morocco, and the contribution of Arab women directors to global cinema and to a gendered understanding of Muslim ethics and aesthetics in film.

A pioneer in Moroccan cinema, Farida Benlyazid has been successful at negotiating the sometimes abrupt turns of Morocco's rocky 20th century history: from Morocco under French occupation to the advent of Moroccan independence in 1956; the end of the international status of Tangier, her native city, in 1959; the "years of lead" under the reign of Hassan II; and finally Mohamed VI's current reign since 1999. As a result, she has a long view of Morocco's politics of self-representation as well as of the representation of Moroccan women on screen.

30 May 2024

DIASPORAS: Quézia Lopes: Corpos Invisíveis (Invisible Bodies) - Festival international du film João Pessoa, à Paraíba

https://www.corposinvisiveis.com.br

Sinopse | Synopsis

O documentário aborda o apagamento social dos corpos negros femininos a partir da experiência pessoal e artística de 11 mulheres negras, que debatem identidade, memória coletiva, ancestralidade, afetividades e maternidade. A partir de entrevistas e performances, afirmam-se como corpos políticos que visibilizam suas muitas formas de ser, existir e resistir, ao passo que respondem à pergunta: o que é ser mulher negra no Brasil?

The documentary “Corpos Invisíveis” addresses the social erasure of black female bodies from the personal and artistic experience of eleven black women, who debate identity, collective memory, ancestry, affections and motherhood. Based on interviews and performances, they assert themselves as political bodies that make their many ways of being, existing and resisting visible, while answering the question: what does it mean to be a black woman in Brazil?

24 May 2024

Simisolaoluwa Akande: The Archive – Queer Nigerians - Festival de Cine Africano Tarifa - Tanger (FCAT) 2024

Simisolaoluwa Akande

The Archive – Queer Nigerians

Experimental - United Kingdom - 2023 - 24′

SINOPSIS

La historia de los nigerianos queer ha sido borrada de la narrativa nacional de Nigeria, por lo que los nigerianos queer del Reino Unido se reúnen para contar sus historias y documentar sus experiencias para que no vuelvan a ser olvidadas.

SYNOPSIS

With Nigerians queer history erased from the national narrative of Nigeria, queer Nigerians in the UK gather to tell stories, documenting their experiences so they can never be erased again.

SYNOPSIS

L’histoire des homosexuels nigérians ayant été effacée du récit national du Nigeria, les Nigérians homosexuels du Royaume-Uni se réunissent pour raconter leurs histoires et documenter leurs expériences afin qu’elles ne soient plus jamais oubliées.

Festival de Cine Africano-FCAT 2024 - Le cinéma réalisé par des femmes et les afroféminismes - Cinema by women and afrofeminisms

Farida Benlyazid and Moroccan Cinema by Florence Martin presented at the Festival de Cine Africano-FCAT

Farida Benlyazid and Moroccan Cinema by Florence Martin presented at the Festival de Cine Africano-FCATBlog Archive

-

►

2009

(34)

- ► March 2009 (4)

- ► April 2009 (5)

- ► August 2009 (2)

- ► September 2009 (1)

- ► October 2009 (3)

- ► November 2009 (2)

- ► December 2009 (3)

-

►

2010

(75)

- ► January 2010 (2)

- ► February 2010 (2)

- ► March 2010 (4)

- ► April 2010 (2)

- ► August 2010 (10)

- ► September 2010 (9)

- ► October 2010 (9)

- ► November 2010 (9)

- ► December 2010 (5)

-

►

2011

(145)

- ► January 2011 (6)

- ► February 2011 (22)

- ► March 2011 (8)

- ► April 2011 (14)

- ► August 2011 (12)

- ► September 2011 (7)

- ► October 2011 (15)

- ► November 2011 (10)

- ► December 2011 (28)

-

►

2012

(124)

- ► January 2012 (10)

- ► February 2012 (12)

- ► March 2012 (15)

- ► April 2012 (10)

- ► August 2012 (2)

- ► September 2012 (18)

- ► October 2012 (8)

- ► November 2012 (9)

- ► December 2012 (14)

-

►

2013

(133)

- ► January 2013 (19)

- ► February 2013 (22)

- ► March 2013 (12)

- ► April 2013 (5)

- ► August 2013 (10)

- ► September 2013 (7)

- ► October 2013 (13)

- ► November 2013 (15)

- ► December 2013 (9)

-

►

2014

(121)

- ► January 2014 (5)

- ► February 2014 (4)

- ► March 2014 (6)

- ► April 2014 (7)

- ► August 2014 (10)

- ► September 2014 (14)

- ► October 2014 (9)

- ► November 2014 (14)

- ► December 2014 (18)

-

►

2015

(165)

- ► January 2015 (10)

- ► February 2015 (29)

- ► March 2015 (31)

- ► April 2015 (17)

- ► August 2015 (4)

- ► September 2015 (19)

- ► October 2015 (16)

- ► November 2015 (9)

- ► December 2015 (12)

-

►

2016

(156)

- ► January 2016 (10)

- ► February 2016 (25)

- ► March 2016 (20)

- ► April 2016 (13)

- ► August 2016 (7)

- ► September 2016 (4)

- ► October 2016 (13)

- ► November 2016 (9)

- ► December 2016 (15)

-

►

2017

(184)

- ► January 2017 (7)

- ► February 2017 (35)

- ► March 2017 (35)

- ► April 2017 (18)

- ► August 2017 (5)

- ► September 2017 (7)

- ► October 2017 (9)

- ► November 2017 (15)

- ► December 2017 (9)

-

►

2018

(152)

- ► January 2018 (12)

- ► February 2018 (9)

- ► March 2018 (11)

- ► April 2018 (7)

- ► August 2018 (8)

- ► September 2018 (7)

- ► October 2018 (22)

- ► November 2018 (12)

- ► December 2018 (4)

-

►

2019

(167)

- ► January 2019 (13)

- ► February 2019 (50)

- ► March 2019 (23)

- ► April 2019 (10)

- ► August 2019 (3)

- ► September 2019 (15)

- ► October 2019 (20)

- ► November 2019 (9)

- ► December 2019 (6)

-

►

2020

(142)

- ► January 2020 (13)

- ► February 2020 (40)

- ► March 2020 (4)

- ► April 2020 (6)

- ► August 2020 (7)

- ► September 2020 (7)

- ► October 2020 (9)

- ► November 2020 (8)

- ► December 2020 (16)

-

►

2021

(191)

- ► January 2021 (12)

- ► February 2021 (17)

- ► March 2021 (19)

- ► April 2021 (17)

- ► August 2021 (14)

- ► September 2021 (8)

- ► October 2021 (45)

- ► November 2021 (15)

- ► December 2021 (19)

-

►

2022

(152)

- ► January 2022 (11)

- ► February 2022 (34)

- ► March 2022 (14)

- ► April 2022 (9)

- ► August 2022 (8)

- ► September 2022 (19)

- ► October 2022 (17)

- ► November 2022 (8)

- ► December 2022 (8)

-

►

2023

(133)

- ► January 2023 (43)

- ► February 2023 (17)

- ► March 2023 (9)

- ► April 2023 (6)

- ► August 2023 (7)

- ► September 2023 (10)

- ► October 2023 (5)

- ► November 2023 (10)

- ► December 2023 (7)

-

▼

2024

(49)

- ► January 2024 (4)

- ► February 2024 (8)

- ► March 2024 (6)

- ► April 2024 (4)

-

►

June 2024

(8)

- Mujeres por África : ELLAS SON CINE 12 - 2024 Madr...

- DIASPORAS : Cinemateca Brasileira apresenta a most...

- Tsitsi Dangarembga (ICAPA), Souad Houssein (OPAC),...

- Ruth Hunduma, laureate of the Hypatia Golden Award...

- Dr. Estrella Sendra discusses the Legacy of Safi F...

- Pauline Mvele Nambané, founding director of the Fe...

- Closeup: The Africas/Diasporas of Women in the Evo...

- Alice Diop filmmaker-sociologist-activist : «Nous...

- ► August 2024 (2)

-

►

September 2024

(6)

- Cine Fem Fest - The African Film and Research Fest...

- Nadine Otsobogo, Filmmaker Make Up Artist is a fea...

- Oscar 2025 : Dahomey de/Mati Diop représentera/wil...

- Seuls en Scène 2024 presents Voyage of the Sable V...

- Focus: Nadia El Fani - Programa de Cortos Nadia El...

- Festival féministe sénégalais - Jotaay Ji - au Mus...

-

►

2025

(41)

- ► January 2025 (3)

- ► February 2025 (8)

- ► March 2025 (3)

- ► April 2025 (3)

- ► August 2025 (7)

- ► September 2025 (1)

- ► October 2025 (2)

- ► November 2025 (2)

- ► December 2025 (5)

-

►

2026

(4)

- ► January 2026 (4)